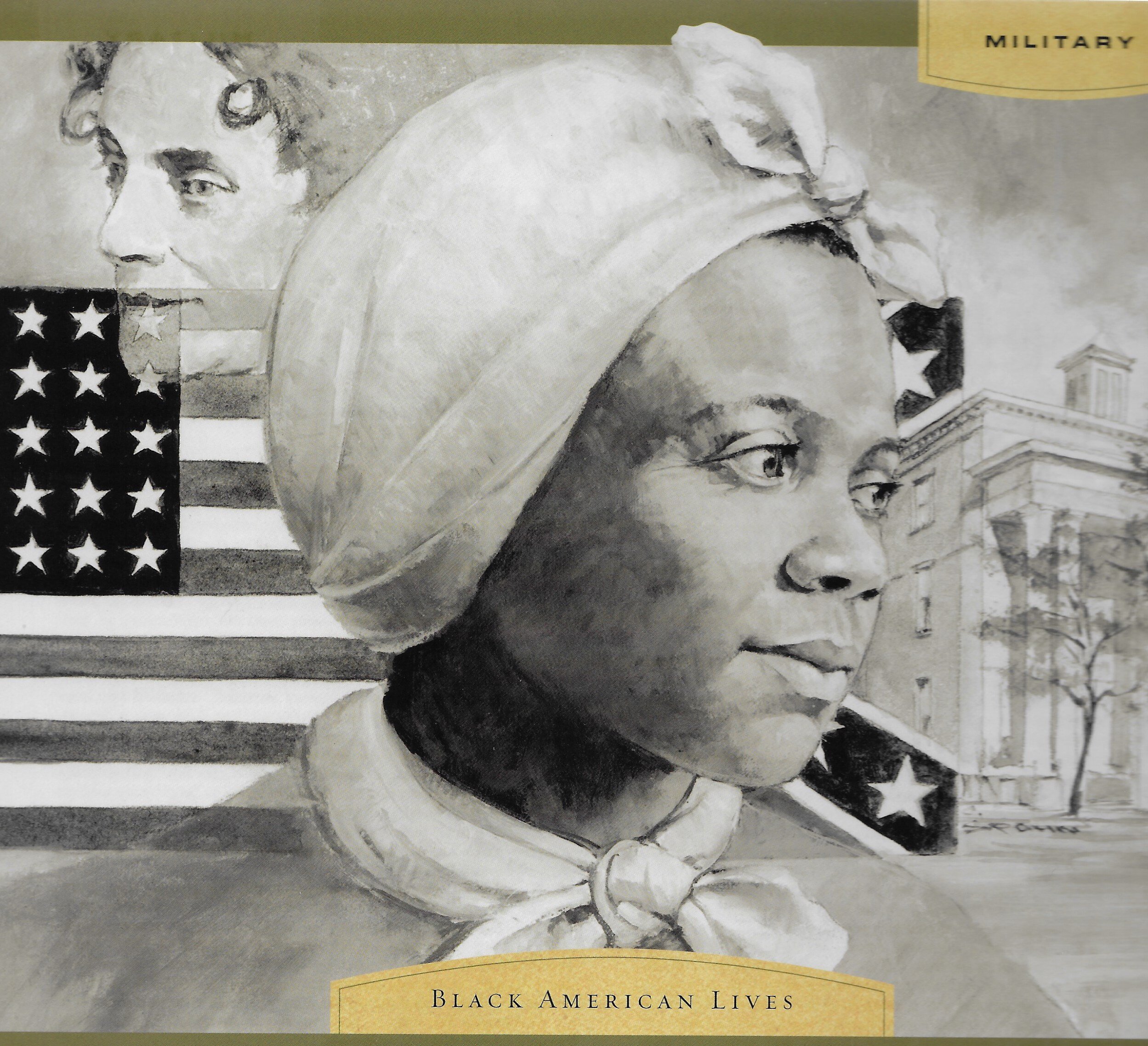

In Touch With Hidden Figures

Two women—one Black, one white—led one of the most important Union spy networks during the Civil War

By Betty Miller Buttram

Of Fort Wayne Ink Spot

Sometimes history has a way of relegating some people into the closet of oblivion. The facts can be unclear which presents a challenge in finding the answers and seeking the truth. Nearly 160 years ago, two women did what they believed in during a particular period in our American history because of the place, the cause, and their connection to each other.

Mary Elizabeth Bowser was born into slavery sometime around 1839 on a Richmond, Virginia plantation owned by John Van Lew, a merchant and farmer. He came to Richmond in 1806 at the age of 16 and within 20 years had built up a prosperous hardware business and owned several slaves. Van Lew died in 1843 and his daughter, Elizabeth Van Lew, took ownership of all his slaves, including Mary Bowser, and subsequently freed them. They were not actually free because this was prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. Elizabeth did not believe in slavery and had become an abolitionist. With no place else to go, the freed slaves stayed on the plantation and were paid by Elizabeth Van Lew for their services.

Elizbeth was born in 1818 in Richmond, Virginia, to John Van Lew and Eliza Baker whose maternal grandfather was abolitionist Hilary Baker, mayor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1796-1798. Elizabeth attended a Quaker School in Philadelphia which reinforced her abolitionist sentiments. Elizbeth felt that Mary had much more significant promise for life beyond domestic help and arranged for her to board in Philadelphia and attend the Quaker School for Negroes.

Mary learned to read, write, and was taught the fundamental elements of a classical education. She was exposed to the northern intellectuals’ sentiments about abolishing slavery and the mounting tensions between the North and the South about the enslavement of her people who made plantation owners wealthy off their labor. Mary Bowser became an abolitionist like her benefactor, Elizabeth. After graduating, Mary returned to Richmond on the eve of the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861.

Upon the outbreak of the war, Elizabeth Van Lew, along with her mother, began work on behalf of the Union, caring for the wounded Union soldiers imprisoned there. Then Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate, decided to move his headquarters from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond. This did not sit too well with Elizabeth. Richmond was a hotbed of organized spies and abolitionist sympathizers and that enabled Elizabeth to build and operate an extensive spy ring for the Union Army during the war.

Davis’ wife, Varina, was tasked with organizing a steady schedule of social events at the Confederate White House and that required the help of many servants at these gatherings. Elizabeth, being a woman of prominence and money in Richmond, recommended Mary Bowser as a possible servant. Using the name “Ellen Bond,” Bowser was first taken on as a servant for these parties, and eventually as a full-time servant inside the Davis household and that began one of the many operations of Elizabeth’s “Richmond Underground” spy network. The Union’s chief spy was a baker named Thomas McNiven who oversaw operations from his centrally located bakery. He worked in close contact with Van Lew and with other spy operatives. McNiven became Mary’s contact person.

Bowser had a good work ethic and played her part as a dim-witted servant. She was viewed as valuable but non-threatening and frequently gained access to Davis’ private quarters and office. She read his correspondence or notations on troop movements and supply lines. Mary passed that intelligence on to Thomas when he made his daily bakery trips to the house. Meanwhile, Van Lew used her home to hide Union soldiers who had escaped from a nearby prison until escape routes could be planned for them.

The Richmond Spy network remained free from detection for much of the war. In January 1865, letters arrived for Davis confirming that there was a spy within his household. Mary Bowser fled under the cover of darkness, and it is said that she was so committed to the Union cause, that she attempted, unsuccessfully, to burn down the house on her departure.

After the end of the Civil War and after the Reconstruction period, Elizabeth Van Lew was increasingly ostracized in Richmond and the neighborhood children were told to consider her a witch. Even into the 20th century, many Southerners regarded her as a traitor.

Having spent her family’s fortune on intelligence activities during the war, she tried in vain to be reimbursed by the federal government and that failed. She attempted to secure a government pension and that also failed. In the end family and friends of the Union soldiers whom she had helped came to her financial aid. Elizabeth Van Lew died on September 25, 1900, and was buried in Richmond’s Shocke Cemetery. Relatives of a Union Colonel donated the tombstone.

No records exist to indicate Bowser’s fate after the end of the war. Some reported that after the fall of Richmond, Mary Bowser worked as a teacher to former slaves in the city, that she traveled to Liberia and gave lectures on her wartime exploits. It is known that she survived long enough to write a memoir of her adventures, but it was mistakenly discarded in the 1950s. Her date of death is unknown.

There are some historians who have done their research on the subject of Elizabeth Van Lew and Mary Bowser and have reported that there is no evidence that either one attended a Quaker school; it is not known whether Mary Bowser infiltrated the Confederate White House as a permanent servant; although Mary used numerous pseudonyms, the name “Ellen Bond” was not one of them; and they doubted the existence of the memoir because it was unlikely a spy would keep such a dangerous document.

U.S. government records of operations and achievements were destroyed after the Civil War, but several accounts survived in the form of records, diaries and oral histories left by McNiven and Van Lew. Both accounts identify Bowser as perhaps the single most critical source of information coming from the Richmond spy network and that provided essential information for the decisions that General Ulysses S. Grant made in battling Confederate troops.

So, wherein, lies the truth. Two women, one a white abolitionist and the other a freed slave joining together for the same cause by committing espionage for the Union Army.

Something must be right about that information provided by McNiven and Van Lew because in 1993, Elizabeth Van Lew was inducted into the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame in Fort Huachuca, Arizona. In 1995, Mary Elizabeth Bowser was also officially inducted into the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame.

A white female abolitionist and a female free slave became spies for the Union Army. That might be a reason to keep Elizabeth Van Lew and Mary Elizabeth Bowser in the closet of oblivion.

But this is Women’s History Month, so open that door and let them out.